The sea is an important resource. It is essential when we work at sea that we protect it by using it sustainably.

The main aim of the Outer Thames Estuary REC study was to create reference material for those involved in the management and development of offshore resources, enabling them to make important decisions about how we used these resources sustainably.

The main aim of the Outer Thames Estuary REC study was to create reference material for those involved in the management and development of offshore resources, enabling them to make important decisions about how we used these resources sustainably.

The Outer Thames Estuary REC study produced regional maps and scientific information detailing the ecology, archaeology and geology of the seafloor. This will help make decisions on how we use the sea, without damaging its natural environment or heritage.

The Outer Thames Estuary REC Conclusions and Recommendations

This section sets out some of the conclusions made by the ecologists, archaeologists and geologists through their scientific research. It highlights some of the most interesting aspects of the Outer Thames Estuary REC study area, and some of the advice given to help protect our seas for the future.

Click on links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

Visit the Outer Thames Estuary REC menu and investigate the ecological, archaeological and geological research results.

[jwplayer mediaid=”3885″]

Protecting Habitats

Protecting Habitats

The Outer Thames REC study has identified some marine habitats in the area which may require protection by law.

Annex I of the European Commission’s Habitats Directive lists habitats that are subject to special requirements for conservation under European Union law.

As a member of the European Union, the Habitats Directive also applies in the United Kingdom law.

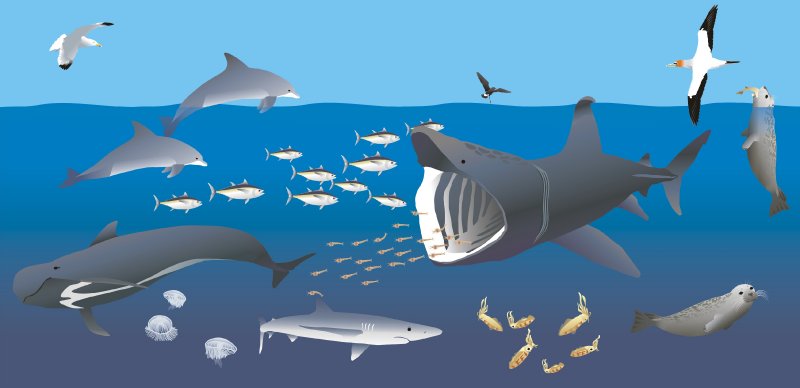

The habitat categories on this list represent key environments that are important to the health and productivity of marine ecosystems. Some habitats play an important role in a sea animal’s life, for example by providing breeding or nursery grounds, while others are homes for fragile or rare seafloor communities. Many marine habitats are under threat from humans’ use of the sea and so require protection.

The government selects a representative proportion of habitats to protect, taken from each habitat category on the Habitats Directive list. The new name for these areas will be Marine Conservation Zones, set up under the government’s Marine and Coastal Act 2009.

Scientists will monitor these Marine Conservation Zones and many activities that might damage these areas will not be allowed.

Ecologists identified a number of habitats that fit two of the Annex I habitat categories in different places across the Outer Thames study area. These categories were sandbanks and biogenic reefs.

The REC findings on the distribution of different marine habitats will help inform government decisions on establishing Marine Conservation Zones in this area.

When is a reef a reef?

When is a reef a reef?

This was one of the questions for the ecologists examining Ross worms in the Outer Thames study area.

Ross worms were one of the most common species found in both the Hamon Grab and Beam Trawl samples.

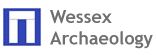

In the section above, we mentioned that biogenic reefs, like those made by Ross worms, are important habitats. The ecologists assessed the ‘reefiness’ of the Outer Thames study area, and mapped the main areas.

So how do they build their homes? The worms like stable gravelly seafloors to attach their homes to. However they also need sand, to build little tubes which they cement together to construct the reef.

Ross worms can live alone but it is only where they live in groups that we find large reefs. In the Outer Thames, the underwater camera images showed that the structures built by the worms were quite patchy at times. This led to the question of whether they are biogenic reefs, as defined in the Annex I habitats list.

The Outer Thames ecologists looked at methods for making this assessment, as well as developing their own. They concluded that more research is required.

As this chart below shows they examined the REC geophysical survey images and identified features on these images that may be reefs.

Inner Gabbard Deeps

Inner Gabbard Deeps

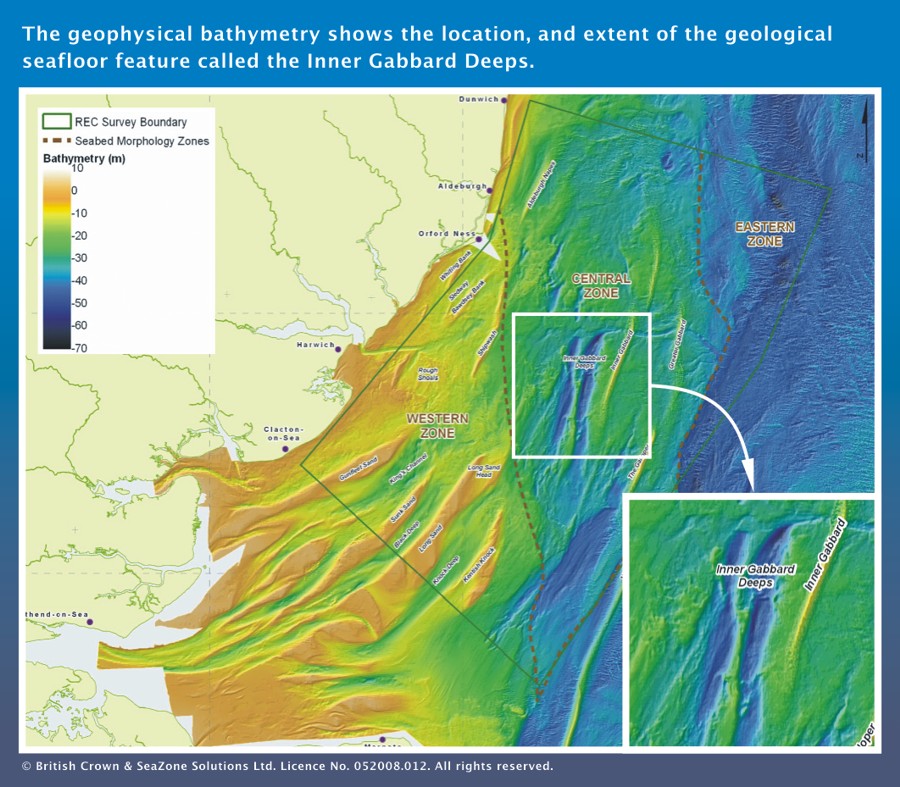

Geologists studied deep channels in the seafloor called the Inner Gabbard Deeps.

The Inner Gabbard Deeps are two 2 kilometre-wide parallel troughs. An 11-kilometre ridge separates them. At their deepest, they are 30 metres deeper than the surrounding seafloor.

Geologists have debated the origins of these channels – there are two theories.

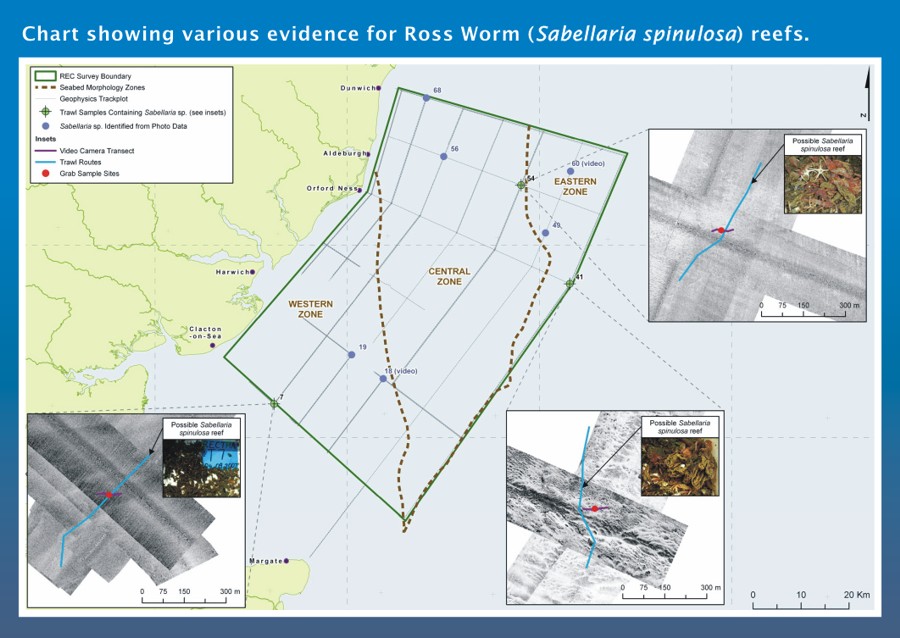

The first is that the melting of the glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age formed them, the water carving out the seafloor.

The second and more probable theory is that they were created earlier, before the glaciers melted.

Underneath the glacier, water remains liquid. This is because the pressure of all the weight of ice lowers the melting point to below 0o Centigrade. This water moves around underneath and beyond the glacier, creating rivers that carve channels into the land.

At this time, the Outer Thames Estuary would have been dry land, not sea. These channels would have been full of water. As the climate grew warmer and the sea levels rose, they were partially infilled with seafloor sediments.

Deep channels are places of refuge for sea animals, as they are protected from the open sea and from human activity.