Archaeologists investigated the East Coast seafloor to find out what it can tell us about the past. They discovered evidence of ancient landscapes and shipwrecks, lying deep below the waves.

Archaeologists investigated the East Coast seafloor to find out what it can tell us about the past. They discovered evidence of ancient landscapes and shipwrecks, lying deep below the waves.

To collect information, archaeologists use a variety of geophysical and sediment sampling techniques that are also used by geologists and ecologists, including collecting sediment samples using a vibrocorer. Marine geophysicists who specialise in archaeology assess the geophysical survey data collected during the REC surveys.

The East Coast REC Archaeological Results

This section provides a summary of the East Coast REC results for the archaeological research.

Click on links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

- Did you know people once lived on the East Coast seafloor?

- Prehistoric climate change timescale

- Discovering Britain’s prehistoric past

- Finding ship and aircraft wrecks

- How important is a shipwreck?

You can find out more about the scientific research techniques mentioned in the text by visiting the “How we study seafloor” webpages.

Read our Sustainability webpages to discover how the results will help protect the East Coast REC area.

Did you know that people once lived on the East Coast seafloor?

One of the key tasks for the REC archaeologists was to assess the potential for finding prehistoric evidence within the sediments beneath the seafloor. To do this they need to understand how the climate changed over the past million years.

Understanding past climate change

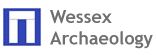

During the last 2.5 million years, known as the Pleistocene on the geological timescale, there have been numerous cold periods, called ‘glacials’ separated by warmer periods called ‘interglacials’. Archaeologists are particularly interested in the last 1 million years when our ancestors are known to have occupied Britain.

During the cold phases large continental ice sheets covered much of Britain and most of the north-west European peninsula.

During warm periods the sea-levels were similar to those today and Britain was an island. However, during cooler periods where water was locked up in ice sheets the sea-level was lower than today. Britain was not an island but a peninsula, joined to continental Europe. During these cooler times, our early ancestors were able to occupy large parts of the peninsula, now submerged beneath the sea.

At the end of the last glaciation, around 12,000 years ago, the climate became warmer so people could live on the peninsula. Then, as the glaciers melted, the sea level rose and gradually flooded many places where people had lived. Geologists refer to the past 10,000 years as the Holocene.

Watch our film to see how the coastline of Britain changed over the past 20,000 years.

[jwplayer mediaid=”4061″]

This means that in the past people could live in the East Coast REC study area. However, what evidence do we have that they did?

Prehistoric climate change timescale

Discovering Britain’s prehistoric past

Discovering Britain’s prehistoric past

Archaeologists use a variety of techniques to examine the evidence of prehistoric remains hidden on and below the East Coast seafloor.

This seafloor archaeological evidence dates to the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. These are terms for periods of prehistory. Check out our Prehistoric climate change timechart above to see how they fit into what happened during the Pleistocene and Holocene.

The geophysical survey data helps archaeologists to build a picture of how the landscape looked in the past, before it was modified by the sea’s currents and movement of seafloor sediments.

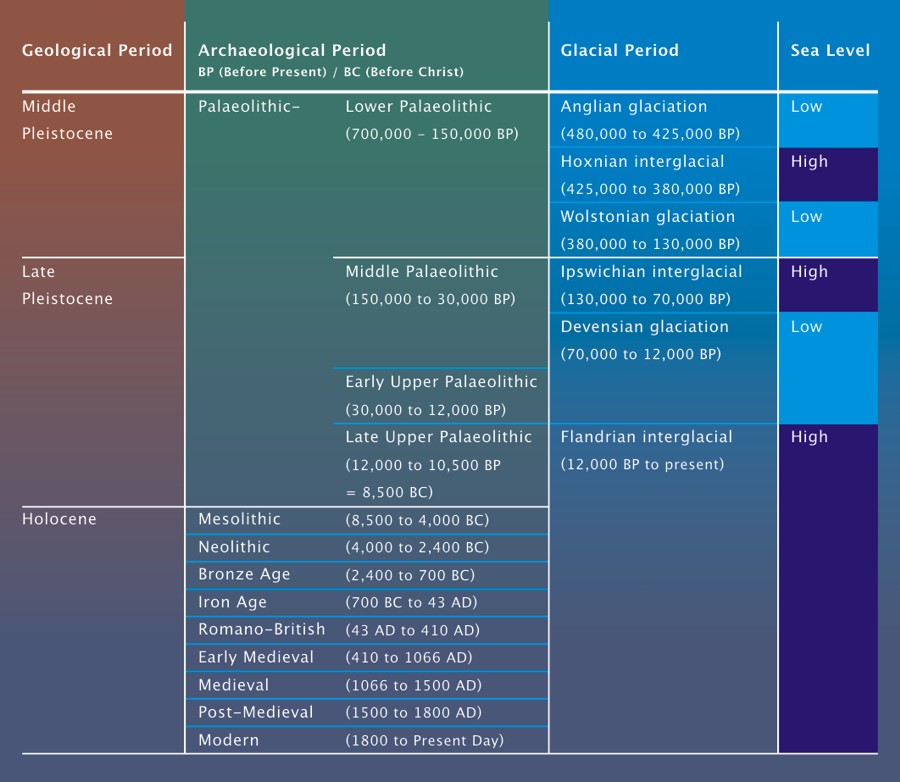

Marine geophysicists examined the geophysical survey data for features, such as river channels cut and then filled during the Pleistocene and Holocene. Preserved within such deposits you can find environmental remains, such as seeds and animal shells. From studying the environmental remains discovered in vibrocore samples of the infill deposits, archaeologists could build a picture of the vegetation of this past landscape. In the East Coast study area, they discovered that from 12,000 to 9,000 years ago, this area was mainly a lowland grass plain.

River channel features are also important for archaeologists to identify evidence of our ancestors. As people need water to live, and as rivers were the main transport routes in prehistory, river features are useful places to start looking for archaeological evidence for Britain’s prehistoric past.

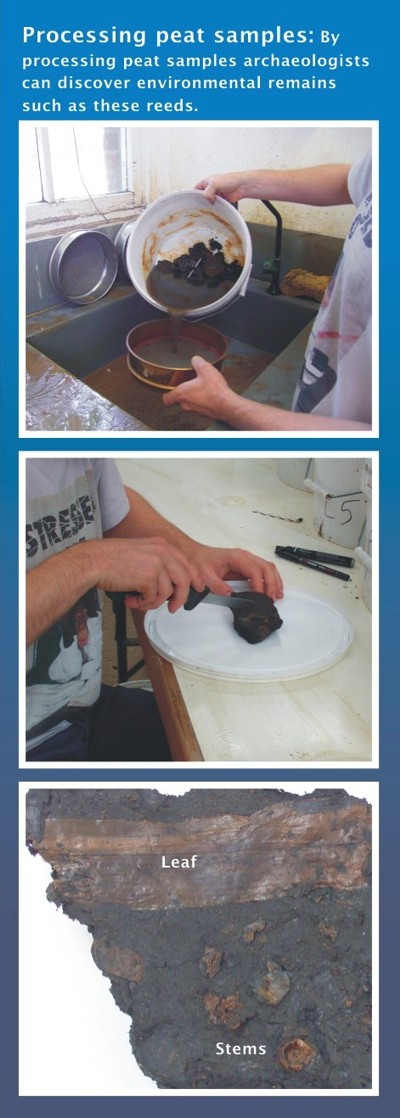

For example, in 2007 and 2008 numerous Middle Palaeolithic stone tools were discovered mixed in with seafloor gravel collected by dredgers in the East Coast study area. The stone tools are probably associated with sediments that were deposited in what was an outer estuary around 250,000 years ago. You can discover more about these finds on the Sustainability webpages.

Finding ship and aircraft wrecks

Finding ship and aircraft wrecks

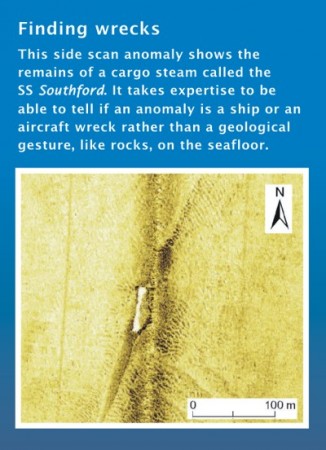

Geophysical survey allows archaeologists to discover amazing things that survive on the East Coast seafloor, including ship and aircraft wrecks.

It is impossible for divers to examine every part of the seafloor for wrecks. Not only is it expensive and very time-consuming, but the dark British waters make the task difficult.

To assess the potential for wrecks in the East Coast study area, the marine geophysicists examined the geophysical survey data, which mapped what the seafloor looks like from a boat. They look out for anomalies, bumps in the seafloor, that may be ship or aircraft wrecks.

The geophysical survey did not cover the whole study area, but the results give a good idea of the number of shipwrecks that survive in the East Coast region.

Archaeologists identified 54 anomalies that match with historical records of known shipwrecks, as well as three possible new shipwreck sites. No aircraft wrecks were found in the East Coast study area.

Post-1815 Shipwrecks

Post-1815 Shipwrecks

All the shipwrecks found in the study area date from 1815 onwards. The seafloor can sometimes cover over older and less obvious ships, and often they do not survive as well as ships that are more modern.

Many of the shipwrecks date to World War I. This is because the study area is close to the harbours of Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft, which were strategically important during the war.

German mine-laying submarines sank many of these boats. They waited underwater near the coastline to attack passing ships. In 1915, the SS Cottingham ran into a German submarine, which revealed this German tactic to the allies. The wreck of this particular submarine lies on the edge of the East Coast REC study area.

The geology results showed that seafloor sediments are very mobile in this area and so buried shipwrecks could become uncovered in the future.

Check out our Sustainability webpages to find out more about shipwrecks.

How important is a shipwreck?

One of the tasks for the East Coast archaeologists was to assess the importance of individual known shipwrecks.

There are several criteria for assessing the historical importance of a shipwreck. It depends what its potential is for telling us about the past; some ships are so important that they are protected by law.

A shipwreck can be a time capsule, recording everything that was happening on the ship – and the technology of the time – when it sank.

The 18th and 19th centuries were a time of innovation in shipbuilding; technological change was rapid. In some cases, a type of ship was only around for a short time before the invention of a new version. Many ships were taken apart to build new ships. Sometimes shipwrecks are the only examples left of their type and can tell us a lot about how shipbuilding changed.

In other cases, it is the stories that are attached to the ship and the part it played in history that makes it important.

During both World War I and World War II , many ships sank, and some are the final resting place of those who fought or worked on these ships. These are protected places, as they are war graves.

The East Coast archaeologists assessed those shipwrecks whose identity or types were known, to help us understand their importance. This will inform future measures to protect them as a record of our maritime heritage.