Archaeologists investigated the Humber seafloor to find out what it can tell us about the past. They discovered evidence of ancient landscapes and shipwrecks, lying deep below the waves.

Archaeologists investigated the Humber seafloor to find out what it can tell us about the past. They discovered evidence of ancient landscapes and shipwrecks, lying deep below the waves.

To collect information, archaeologists use a variety of geophysical and sediment sampling techniques that are also used by geologists and ecologists, including collecting sediment samples using a vibrocorer. Marine geophysicists who specialise in archaeology assess the geophysical survey data collected during the REC surveys.

The Humber REC Archaeological Results

This section provides a summary of the Humber REC results for the archaeological research.

Click on links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

- Did you know people once lived on the Humber seafloor?

- Prehistoric climate change timechart

- Discovering Britain’s prehistoric past

- Finding ship and aircraft wrecks

- Tales from the sea

You can find out more about the scientific research techniques mentioned in the text by visiting the “How we study seafloor” webpages.

Read our Sustainability webpages to discover how the results will help protect the Humber REC area.

Did you know that people once lived on the Humber seafloor?

One of the key tasks for the REC archaeologists was to assess the potential for finding prehistoric evidence within the sediments beneath the seafloor. To do this they need to understand how the climate changed over the past million years.

Understanding past climate change

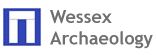

During the last 2.5 million years, known as the Pleistocene on the geological timescale, there have been numerous cold periods called ‘glacials’ separated by warmer periods called ‘interglacials’. Archaeologists are particularly interested in the last 1 million years when our ancestors are known to have occupied Britain.

During the cold phases large continental ice sheets covered much of Britain and most of the north-west European peninsula.

During warm periods, the sea-levels were similar to those today and Britain was an island. However, during cooler periods, when water was locked up in ice sheets, the sea-level was lower than today, and Britain was not an island but a peninsula, joined to continental Europe. During these cooler times, our early ancestors were able to occupy large parts of the peninsula, now submerged beneath the sea.

At the end of the last glaciation, around 12,000 years ago, the climate became warmer so people could live on the peninsula. Then, as the glaciers melted, the sea level rose and gradually flooded many places where people had lived. Geologists refer to the last 10,000 years as the Holocene.

Watch our film to see how the coastline of Britain changed over the past 20,000 years.

[jwplayer mediaid=”4061″]

This means that in the past people could live in the Humber REC study area. However, what evidence do we have that they did?

Prehistoric climate change timescale

Discovering Britain’s prehistoric past

Discovering Britain’s prehistoric past

Archaeologists use a variety of techniques to examine the evidence for prehistoric remains hidden on and below the Humber study area seafloor.

This seafloor archaeological evidence dates to the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods of prehistory. Check out our Prehistoric Climate Change timechart above to see how they fit into what happened during the Pleistocene and Holocene.

The geophysical survey data helps archaeologists to build a picture of how the landscape looked in the past, before it was modified by the sea’s currents and movement of seafloor sediments.

Marine geophysicists examined the geophysical survey data for features such as river channels cut and then filled with seafloor deposits during the Pleistocene and Holocene. Preserved within such deposits you can find environmental remains, such as seeds and animal shells.

Archaeologists take samples of these deposits from underneath the seafloor surface using a vibrocorer. Peat is sometimes found. Peat is formed from plant material that once grew when the study area was dry land; its presence tells us that an area was once marshy – a good place for people to find food and other resources.

The environmental evidence from cores, for example seeds and small animal shells, can give us a picture of the landscape at that time, for example what plants were growing.

You can sometimes discover archaeological artefacts. For example, an antler harpoon was discovered in a block of peat close to the study area; radiocarbon dating tells us it is about 12,000 years old.

Immediately outside of the Humber study area, there are preserved remains of ancient forests on the seafloor, with artefacts that date them to the Stone Age.

Finding ship and aircraft wrecks

Finding ship and aircraft wrecks

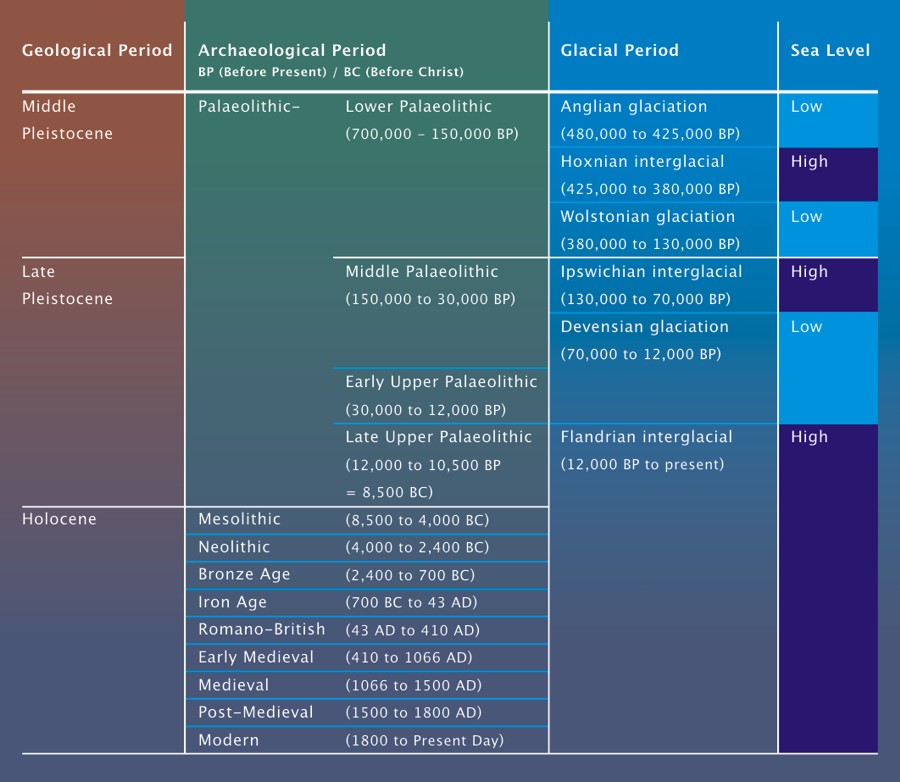

The Humber region has a long and busy maritime history but the seas here can be hazardous. This means there is a high potential for discovering shipwrecks on the seafloor.

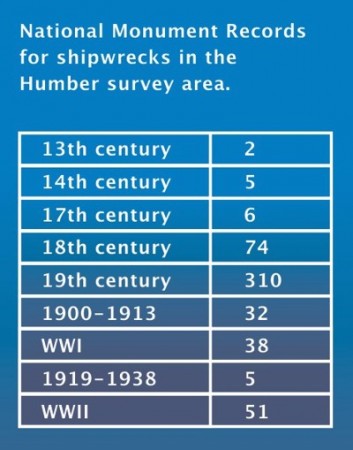

Examining the National Monument Records (NMR) showed that there are 577 known shipwrecks in this area. These date from the 13th century up until World War II.

Finding a record, however, does not always mean that you will find the shipwreck. Medieval documents tell us that in 1255 the German cargo vessel Jacobus sank during a bad storm. This is the earliest known shipwreck in the Humber area. However, the actual wreck remains undiscovered.

There could be several reasons why the ship continues to be a mystery. For example, the record made at the time only gave an estimate of the ship’s location when it sank, or else the remains of the shipwreck have not survived.

Another source of information is the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office database (UKHO), which listed 259 physical shipwrecks in this area. The archaeologists cross-referenced the list with the NMR records, to match up wrecks and discover more about their past.

For example, the UKHO records a wreck position, which we think could be the remains of the Marshal, an early iron steamship. The NMR records show that this ship sank near that location in 1853 after colliding with the Woodhouse, a wooden sailing ship.

Tales from the sea

What was life like on the sea? How did a ship end up on the seafloor?

There are many interesting stories attached to the shipwrecks recorded in the Humber area. The NMR can tell us a lot more than how many wrecks lie on the bottom of the sea; they can also tell us how they ended up there.

In the 19th century, British trade grew and the seas became a busy highway for transporting goods. Competition was fierce, demonstrated by the story of the cargo vessel Isabella and Mary.

On the night of 23rd August 1815, this ship sank while transporting coal from Newcastle to London. A court case a year later tells us it was not an accident. The Newcastle Courant newspaper reported that the ship ‘was run down by the defendant’s ship, the Rolla’. The court fined the defendant, Mr Brown, 5,000 pounds in damages and 40 shillings in costs.

On other occasions, business was too important to stop and help. A schooner called the Fly collided with a ship and then, despite their cries for help, sailed away. Fortunately, a passing ship Neptune rescued the abandoned crew.

There are many more stories like these in the NMR, which bring to life the shipwrecks discovered on the seafloor.