The sea is an important resource. It is essential when we work at sea that we protect it by using it sustainably.

The main aim of the East Coast REC study was to create reference material for those involved in the management and development of offshore resources, enabling them to make important decisions about how we used these resources sustainably.

The main aim of the East Coast REC study was to create reference material for those involved in the management and development of offshore resources, enabling them to make important decisions about how we used these resources sustainably.

The East Coast REC study produced regional maps and scientific information detailing the ecology, archaeology and geology of the seafloor. This will help make decisions on how we use the sea, without damaging its natural environment or heritage.

The East Coast REC Conclusions and Recommendations

This section sets out some of the conclusions made by the ecologists, archaeologists and geologists through their scientific research. It highlights some of the most interesting aspects of the East Coast REC study area, and some of the advice given to help protect our seas for the future.

Click on links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

- Protecting habitats

- Investigating Ross worms

- Watch out for sandbanks!

- The tides of change

- An ancient discovery

Visit the East Coast REC menu and investigate the ecological, archaeological and geological research results.

[jwplayer mediaid=”3885″]

Protecting Habitats

Protecting Habitats

The East Coast REC study has identified some marine habitats in the area that may require protection by law.

Annex I of the European Commission’s Habitats Directive lists habitats that are subject to special requirements for conservation under European Union law.

As a member of the European Union, the Habitats Directive also applies in the United Kingdom law.

The habitat categories on this list represent key environments that are important to the health and productivity of marine ecosystems. Some habitats play an important role in a sea animal’s life, for example by providing breeding or nursery grounds, while others are homes for fragile or rare seafloor communities. Many marine habitats are under threat from humans’ use of sea and so require protection.

Government selects a representative proportion of habitats to protect, taken from each habitat category on the Habitats Directive list. The new name for these areas will be Marine Conservation Zones, set up under the government’s Marine and Coastal Act 2009.

Scientists will monitor these Marine Conservation Zones and many activities that might damage these areas will not be allowed.

Ecologists identified a number of habitats that fit two of the Annex I habitat categories in different places across the East Coast study area. These categories were sandbanks and biogenic reefs.

The REC findings on the distribution of different marine habitats will help inform government decisions on establishing Marine Conservation Zones in this area.

Investigating Ross Worms

Ross worms were the most common species found in the East Coast REC study area.

[jwplayer mediaid=”3880″]

Ecologists counted 12,000 individuals in their Hamon Grab samples, and substantially more in the trawl samples and on the video film of the seafloor.

Ecologists counted 12,000 individuals in their Hamon Grab samples, and substantially more in the trawl samples and on the video film of the seafloor.

Ross worms live in a tube that they build from sand grains they have filtered from the water. They can live alone but usually they like to live together, when their tubes join into a mass that grows in size as the number of worms increases. Sometimes the worm structures can grow to become a ‘reef’, when the structure rises above the seafloor. It takes thousands of Ross worms to build a reef. These reefs can grow to be as large as several hectares in size and up to half a metre thick.

Reefs that are made by animals like this are called biogenic, a word that literally means ‘made by biology’.

Ross worm reefs have lots of gaps and crevices between the tubes that make an excellent habitat for a lots of other sea animals. Because the reefs are important for other animals, these reefs are protected habitats.

However, ecologists need to assess whether the Ross worm structures they find can be classified as a reef. The ecologists assess the ‘reefiness’ of the Ross worm structures in a number of ways: for example by assessing the size and extent using geophysical survey and camera images, and by counting the number of Ross worm animals present. In the REC geophysical survey images, you can see that the reefs are visible, showing that in some areas they are very substantial.

Watch out for sandbanks!

Watch out for sandbanks!

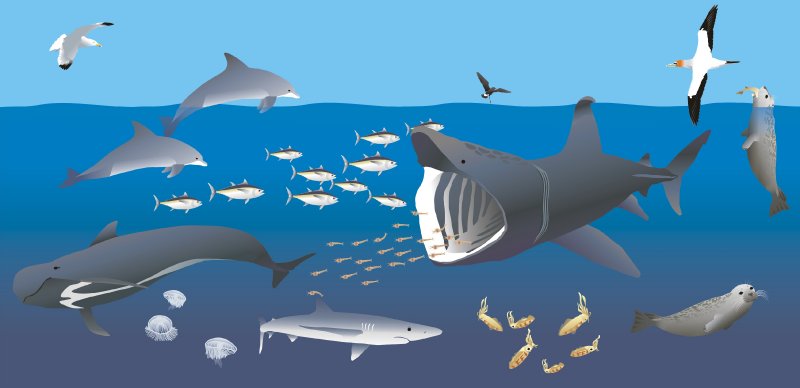

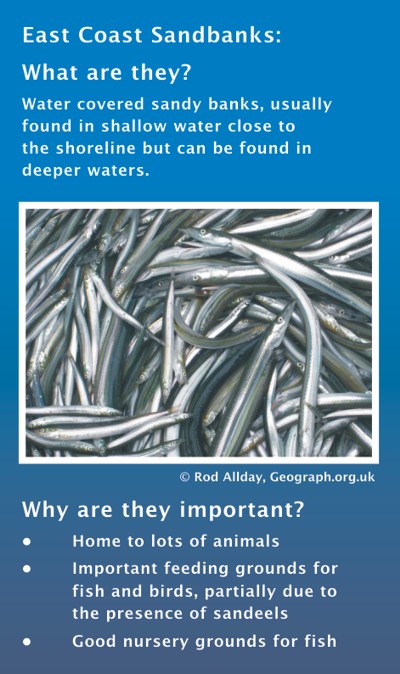

Sandbanks are the largest geological features in the East Coast study area. They can be as big as 50km long, 6km wide and 40m in height.

In the East Coast REC study area, the Great Yarmouth Banks encompass a number of sandbanks, including Scroby Sands and Smith’s Knoll.

Offshore sandbanks can be very large. Smith’s Knoll is approximately 1.7km wide and 20km long. Due to its size and shape, geologists think that this sandbank is one of the oldest in the REC study area.

Near the shore, you can find many sandbanks located close to each other and in some places they are only 2m below the surface of the sea.

One of the tallest sandbanks off the Great Yarmouth coastline is Scroby Sands. It is so tall that sometimes it sticks out of the sea.

One of the tallest sandbanks off the Great Yarmouth coastline is Scroby Sands. It is so tall that sometimes it sticks out of the sea.

Sandbanks located close to the coastline are more mobile. Sea currents can cause the sands that form the bank to move slowly, causing sandbanks to travel. Geologists believe that the Scroby Sands have moved 1.5km north in 150 years.

Sandbanks are therefore a potential hazard for ships, so it is very useful to know their locations.

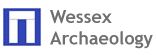

Ecologists highlighted that the East Coast sandbanks provide an excellent habitat for a wide variety of sea animals, including worms, crabs, starfish, sand eels and flatfish.

The tides of change

The tides of change

Archaeologists highlighted two shipwrecks in the East Coast study which illustrate a time of invention and innovation in shipbuilding during the Victorian era.

The SS Seagull is a two-masted paddle schooner, which was built in Belfast by Coates and Young at the Lagan Foundry in 1847. She sank in February 1868 after a disastrous collision. There are few examples of paddle steamers like the SS Seagull, which makes it of particular interest to archaeologists.

The reason paddle steamers are so rare is that propeller- or screw-driven vessels soon superseded them. You can see the differences in the two forms of transport in the illustration below.

Another East Coast shipwreck, the Xanthe, is an example of a screw-driven ship, a steam screw barque built in Hull in 1862. Unfortunately, she also sank after a collision in 1869.

The short era of paddle steamers was a romantic period in our history of maritime travel. It is important that we protect and study such wrecks to understand our past and the development of naval technology during this period of innovation.

An ancient discovery

An ancient discovery

An amazing archaeological discovery was made in the East Coast REC study area.

In February 2008 a Dutch amateur archaeologist, Jan Muelmeester, discovered 88 flint tools and the remains of mammoth, bison, deer and rhino that were dredged from a license dredging area called Area 240, situated 11km off the coast of East Anglia.

The sediments from which the tools were dredged are thought to date to between 250,000 and 140,000 years ago, before the last ice age.

The discovery included thirty-three handaxes and some smaller pieces of flint, known as flakes.

Prior to this discovery many experts believed that marine deposits of this date had been destroyed or disturbed by glaciation. These types of finds are incredibly rare, and there are only a relatively small number of similar sites known on land and – until this – none from the sea around the British Isles.

Since 2008, Wessex Archaeology has undertaken research, using Area 240 as a case study, to develop efficient methods for investigating evidence for prehistoric activity on the seafloor. The evidence from this research was used to re-construct the environment from the time when the tools were being used by our predecessors.

The discovery was so important that the dredging company who reported it won the prestigious British Archaeological Award.