Ecologists studied the animals living in and on the seafloor of the Outer Thames Estuary REC study area. It is important to know what species of animals and how many live in the region, as well as what habitat they like to live in, so that we can protect our amazing coastal sea life.

The focus of the REC research was studying the benthic macrofauna. This term refers to all small animals that live in and on the seafloor.

The focus of the REC research was studying the benthic macrofauna. This term refers to all small animals that live in and on the seafloor.

In the REC results, the ecologists divided them into two main groups, infauna, which are animals that live in the seafloor and epifauna, which live on or just above the seafloor.

They also looked at other larger animals such as fish that live in the area.

Outer Thames Estuary REC Ecology Results

This section provides a summary of the Outer Thames Estuary REC results for the ecological research.

Click on the links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

- What is living in the seafloor?

- What is living on the seafloor?

- Seafloor communities

- Seafloor species: Sand mason worm

You can find our more about the scientific research techniques mentioned in the sections below by visiting our “How we study the seafloor” webpages.

Read our Sustainability webpages to discover how these results will help protect the Outer Thames Estuary REC area.

What is living in the seafloor?

During the REC, ecologists discovered that there are many different animals living in the Outer Thames seafloor.

Working from a boat, the ecologists used a Hamon Grab to collect 70 samples of infauna to study. It is important to note that the Hamon Grab will also collect some epifauna, so often results can contain both type of benthic macrofauna. In total, the ecologists discovered 316 different types of benthic macrofauna.

The ecologists grouped the infauna into different animal types. The most common animal type in the Outer Thames was Annelida, which is a term that describes most marine worms. Each animal type is made up of lots of different species, for example, the Ross worm and the T-headed worm both belong to Annelida.

The ecologists found that the diversity – the number of different species living in one place – varied across the Outer Thames study area.

They discovered that in sandy areas of the seafloor they often found as little as three different animals in a sample.

In seafloor samples from areas where there was a mix of sand, gravel and mud, they found as many as 85 different animals. This is because the mix of sediment provides more options for different sea animals to live there.

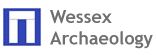

What is living on the Seafloor?

Using trawling nets along the seafloor is another method for exploring the marine life of the Outer Thames seafloor.

Beam Trawls collect fauna that attach themselves to the seafloors and mobile fauna, such as fish and crabs, that all live on or above, rather than in the seafloor. It is important to note that the trawls will also collect some infauna.

The ecologists grouped the epifauna into different animal types. Each animal type is made up of lots of different species, for example, the Ross worm and the T-headed worm both belong to the Annelida.

They then identify all the animals. The trawls identified 18 species of epifauna that attach to surfaces that the Hamon Grab samples did not find. The most common of these was the sea chervil. This species likes to attach itself to stones and they grow in patches all over the Thames Estuary.

For mobile epifauna, the trawls found 72 more species, including shrimp, green sea urchins, flying crab and juvenile gobies.

Once the ecologists identifed each species collected, they looked for different combinations of animals that live together out of the larger epifanua. The ecologists identified a cluster of animals called B1, which included sea anemones and sea squirts. This group prefer to live in areas where the seafloor consists of muddy sand and gravel.

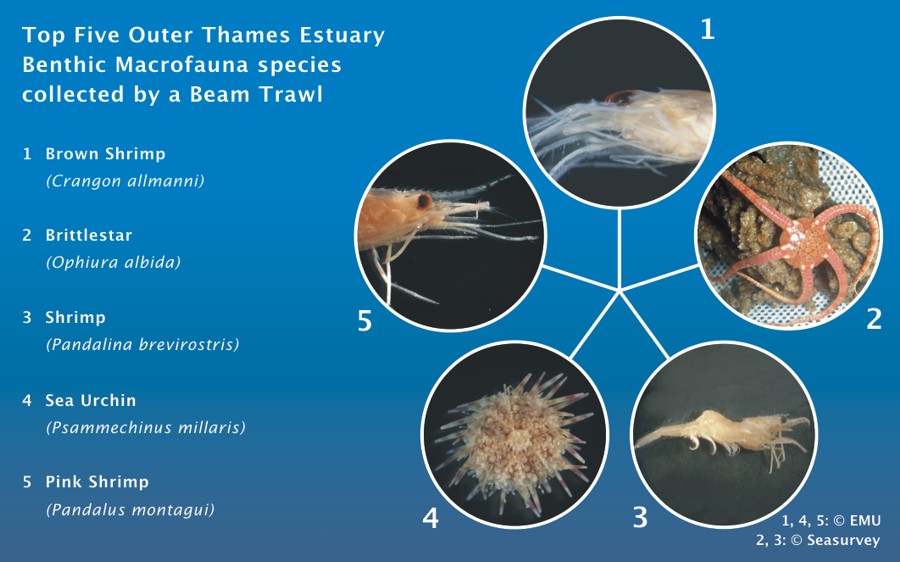

Seafloor communities

Different combinations of animals and plants like to live in different underwater environments. We can think of these groups of animal and plants as seafloor communities.

Understanding seafloor communities and their habitats is important to help us protect sea life in the Outer Thames Estuary area and all around the coast of the United Kingdom.

By gathering together information about seafloor animals and the geology for the area, ecologists are able to map the seafloor communities and their habitats.

This is a complicated process called modelling, which uses computer programs to help predict how the results from our samples stations can tell us about the whole area. This is needed because it is not possible to take grab or trawl samples from everywhere in the study area and we need to fill in the gaps.

Ecologists give each seafloor community and its habitat a classification called a biotope, which provides a description of its key components.

They identified 20 different biotopes in the Outer Thames Estuary area.

This biotope system allows us to predict areas of the seafloor where endangered species live, or where diversity is high, so that we can ensure they are protected. We can also keep an eye on these areas to see how changes, caused by humans or nature, affect the numbers and types of animals present.

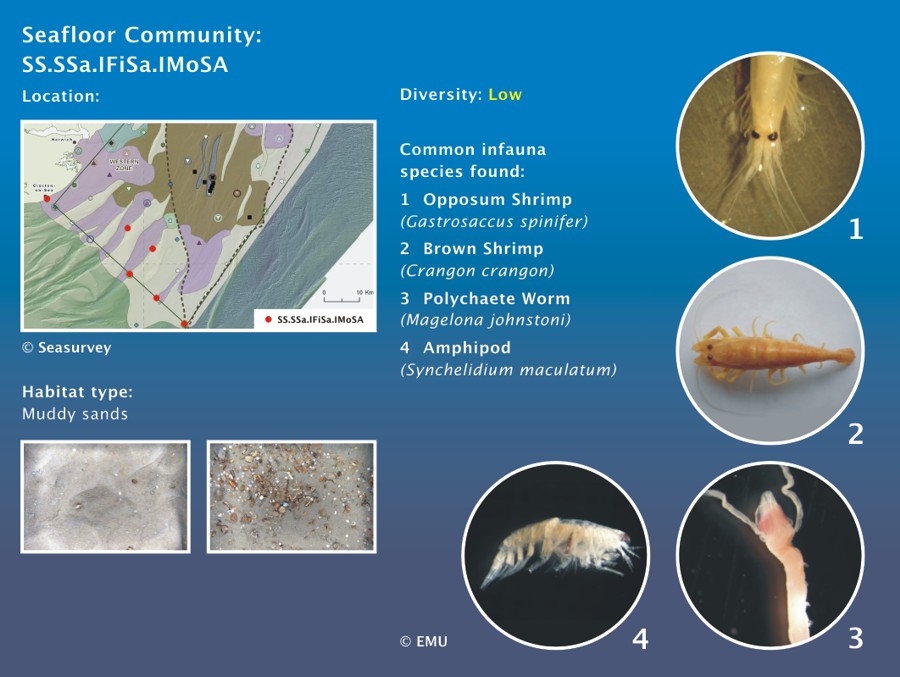

Seafloor species: Sand mason worm