The sea is an important resource. It is essential when we work at sea that we protect it by using it sustainably.

The main aim of the Humber REC study was to create reference material for those involved in the management and development of offshore resources, enabling them to make important decisions about how we used these resources sustainably.

The main aim of the Humber REC study was to create reference material for those involved in the management and development of offshore resources, enabling them to make important decisions about how we used these resources sustainably.

The Humber REC study produced regional maps and scientific information detailing the ecology, archaeology and geology of the seafloor. This will help make decisions on how we use the sea, without damaging its natural environment or heritage.

The Humber REC Conclusions and Recommendations

This section sets out some of the conclusions made by the ecologists, archaeologists and geologists through their scientific research. It highlights some of the most interesting aspects of the Humber REC study area, and some of the advice given to help protect our seas for the future.

Click on links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

Visit the Humber REC menu to investigate the ecological, archaeological and geological research results.

[jwplayer mediaid=”3885″]

Protecting habitats

Protecting habitats

The Humber REC study has identified some marine habitats in the area that may require protection by law.

Annex I of the European Commission’s Habitats Directive lists habitats that are subject to special requirements for conservation under European Union law.

As a member of the European Union, the Habitats Directive also applies in the United Kingdom law.

The habitat categories on this list represent key environments that are important to the health and productivity of marine ecosystems. Some habitats play an important role in a sea animal’s life, for example by providing breeding or nursery grounds, while others are homes for fragile or rare seafloor communities. Many marine habitats are under threat from humans’ use of the sea and so require protection.

The government selects a representative proportion of habitats to protect, taken from each habitat category on the Habitats Directive list. The new name for these areas will be Marine Conservation Zones, set up under the government’s Marine and Coastal Act 2009.

Scientists will monitor these Marine Conservation Zones and many activities that might damage these areas will not be allowed.

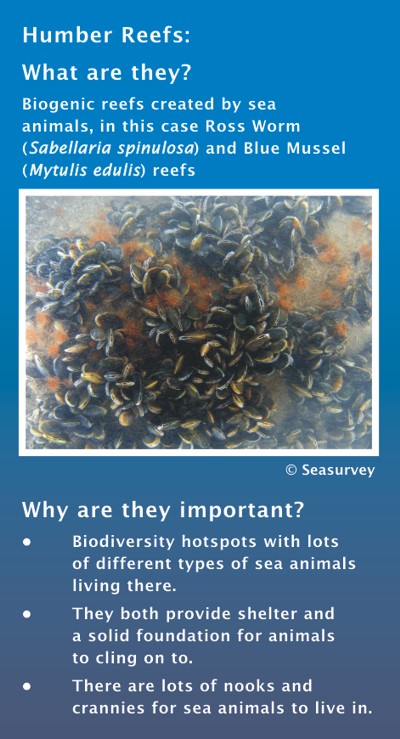

Ecologists identified a number of habitats that fit two of the Annex I habitat categories in different places across the Humber study area. These categories were sandbanks and biogenic reefs.

The REC findings on the distribution of different marine habitats will help inform government decisions on establishing Marine Conservation Zones in this area.

Finding rare and alien species

There were several rare and ‘alien’ or non-native species found in the Humber REC study area. The identification and monitoring of rare and alien species is an important part of conservation management.

Rare species are at risk of extinction and we must develop strategies to ensure that they continue to survive in British waters. The Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) has a set of criteria to assess whether a seafloor species is rare.

Marine alien species are plants or animals that do not originate from the United Kingdom but that do have established populations in our waters.

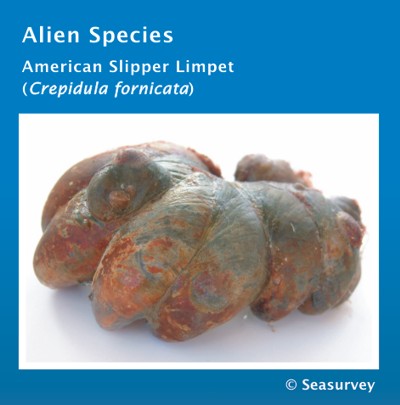

Ecologists identified a type of snail, the American Slipper limpet, as the most common alien species in the Humber study area.

In the 1870s, these limpets came over among American edible oysters and clams, which were being imported and introduced to our coastal waters to boost the English shellfish trade.

These limpets can threaten oyster beds, because they like the same habitats and food. They eat by filtering edible material from the water and they reject the material they do not want. This material forms a layer of fine sediment on the seabed which can smother and kill oysters.

American slipper limpets are now particularly common along the south and south-east coast of the UK. They like relatively warm water and although there are not so many in the Humber area, this is as far north as you will find them in the UK.

Fortunately, the waters of the North Sea are quite cold in the winter and many of the American limpets do not survive. This means that numbers in the Humber area should remain fairly low, although it is important to keep an eye on these and other alien species in the Humber, and in all areas around the UK coastline.

[jwplayer mediaid=”3873″]

Supplying demand

Supplying demand

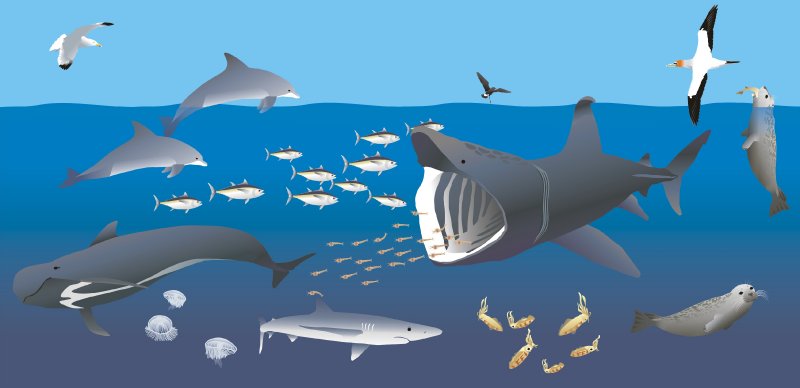

The Humber REC study area is an important area for commercial fishing, for species like cod, whiting and seabass. These fish rely on smaller sea animals for food.

Many of the sea animals living in and on the seafloor are an important food source for birds, fish and mammal predators. Ecologists recognised that many species identified in the Humber REC research have ‘trophic significance’. This means they play an important role in the marine food chain. You can discover more about these sea animals on our Ecology webpages.

For example, the pink shrimp is an important food source for fish and birds. The REC identified some habitats that were particularly good places for pink shrimp to live and breed. These places may be an important link in the food chain that provides us with the fish that we eat.

The Silver Pit is a deep tunnel valley on the Humber seafloor. On the west side of this valley there are Ross worm reefs and on its east side live lots of pink shrimp. In addition, there is a high level of diversity of other sea animals living here.

It is important to monitor places like the Silver Pit, which have important sources of food for other marine animals and birds. Without one element of the food chain, the rest cannot survive. We need to look after these environments so that there is enough food for fish, so that we can fish sustainably.

[jwplayer mediaid=”3882″]

The Reid River

The Reid River is one of the most important discoveries of the Humber REC survey. It represents the study area’s ancient past.

Using geophysical survey data acquired during the REC project, geologists identified and mapped the location of a channel on the seafloor. This channel was once the course of an ancient river.

The geophysical survey recorded the course and depth of the river, and showed that it was part of a series of rivers.

The river was active during the early Holocene period, 10,000 to 8,000 years ago, after the end of the Ice Age, when the area was dry land, before the ice completely melted and sea levels rose to cover the Humber REC area.

Vibrocorer samples of the seafloor sediments, which now fill the river channel, contain environmental evidence about the plants, animals and landscape from when the river was active. Carbon dating of this material shows it is from the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age).

The use of scientific methods allows geologists and archaeologists to understand how the land changed after the end of the last Ice Age. It shows the environment of the prehistoric people who lived on this land, before sea level rise forced them to move.

The results show that this movement of people is more complex than originally thought. Understanding the impacts of climate change on human populations in the past allows us to understand how it may affect us in the future.

HMS Cape Spartel

The REC research highlights shipwrecks of archaeological interest because they represent an important element of our maritime past.

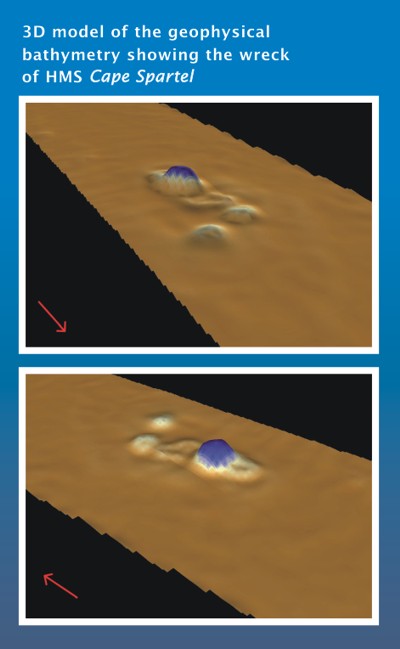

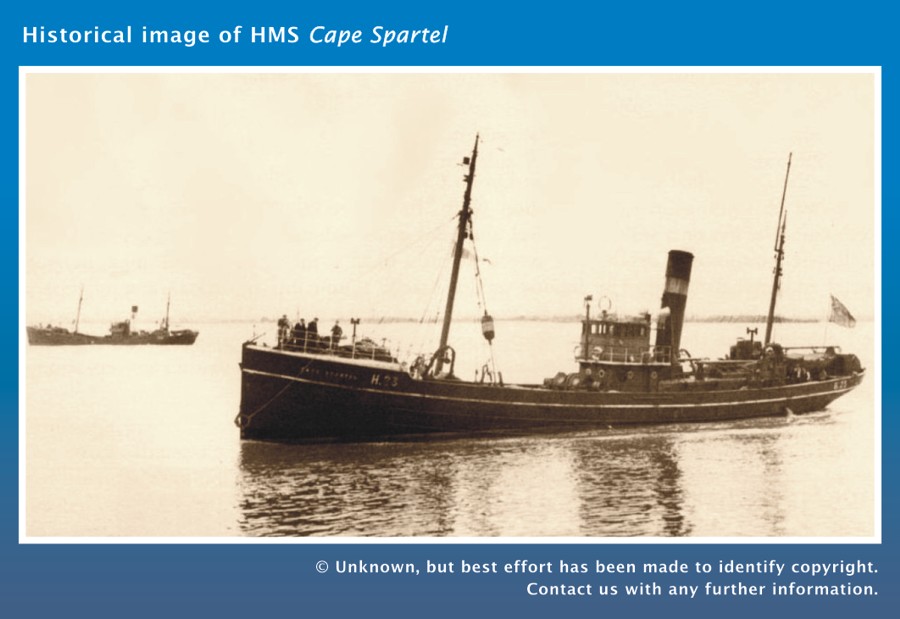

The Humber REC results identified the possible location of the wreck of a steel fishing trawler called the HMS Cape Spartel.

During World War II, the Admiralty requisitioned this ship for the Royal Naval Patrol Service (RNPS). The RNPS consisted of a variety of mainly non-military small boats, who undertook a wide range of tasks supporting the British Navy.

Fishing trawlers, like the Cape Spartel, were useful for minesweeping and escorting larger ships along the coast.

Most of the men in the RNPS were volunteers, known as reservists, who enlisted in the Navy reserve before the war.

Cape Spartel was lost on 2nd February 1942, when a bombing raid of twenty German planes attacked. There was no record of what happened to the crew.

There are several reasons why this wreck is of archaeological importance and should be protected.

Firstly, its use by the military when it sank means it may need to be protected under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986. As it is unclear what happened to the crew, there is a possibility this site is a war grave.

Also, in a wider context this vessel is an example of the important role of the RNPS during World War II.