Archaeologists study the material remains of the past to understand how people lived. Archaeological material from the seafloor can range in date from the Lower Palaeolithic (970,000 BP – Before Present) to World War Two.

Archaeologists study the material remains of the past to understand how people lived. Archaeological material from the seafloor can range in date from the Lower Palaeolithic (970,000 BP – Before Present) to World War Two.

There are two main ways that archaeologists collect data; through their own fieldwork and through reviewing information already available.

Often when people think about underwater archaeologists they think of a SCUBA diver on the seafloor. Working in an underwater environment is a challenge and when excavation does occur it is largely a process of uncovering material buried in seafloor sediments, for example, ship and aircraft wrecks.

Divers will survey ship or aircraft wrecks to record their structure and artefact positions in detail. This is, however, only a small percentage of their work. It is impossible for divers to examine every part of the seafloor; not only is working underwater expensive and very time-consuming, often the low light and visibility in British waters makes it difficult to carry out surveys efficiently.

There are many methods, which archaeologists use to collect data, including desk-based research, geotechnical survey and geophysical survey.

What methods did the REC archaeologists use to study the seafloor?

The REC archaeologists did not undertake any diving fieldwork, but they did use several other methods to find out about Britain’s seafloor heritage. These are described below.

The following section outlines the key methods for studying the archaeology of the REC study areas. Click on the links below to find out about each topic, or scroll down to read the entire text.

- What is a Desk Based Assessment (DBA)?

- Geophysical survey

- Geotechnical survey

- Assessing significance

Although all four RECs use the same key methods, they may have been used in slightly different ways.

What is a Desk Based Assessment (DBA)?

Desk Based Assessments (DBA) are often the first step for archaeologists, both on land and sea, when asked to assess an area for archaeology.

This assessment is required as part of the planning process for certain activities that could affect archaeology underneath the ground or on the seafloor, for example, before installing an offshore windfarm. It allows archaeologists to assess the potential for finding archaeology in that area, based on what is already known for that locality. This helps decisions on what archaeological investigations need to be undertaken next, to ensure that the archaeological material is ‘preserved by record’ or ‘preserved in situ’.

This assessment is required as part of the planning process for certain activities that could affect archaeology underneath the ground or on the seafloor, for example, before installing an offshore windfarm. It allows archaeologists to assess the potential for finding archaeology in that area, based on what is already known for that locality. This helps decisions on what archaeological investigations need to be undertaken next, to ensure that the archaeological material is ‘preserved by record’ or ‘preserved in situ’.

A DBA collects and summarises archaeological information about a defined area in a report, in this case the REC. This includes any relevant research already undertaken and other sources of information about the potential for finding archaeological material in the study area. Often an area, particularly a large one, has been subject to lots of archaeological investigations. A DBA is a useful way of bringing together many individual pieces of work into one place so that it can be referenced easily.

This information is usually created by a variety of different organisations for a variety of reasons. Again, like the survey, the detail the DBA goes into is limited by time, money and the aims of the project. Often DBAs will tell where you can find information, with a brief summary of what it is and its significance, rather than repeat ALL the information in a new report.

Historical sources for wrecks

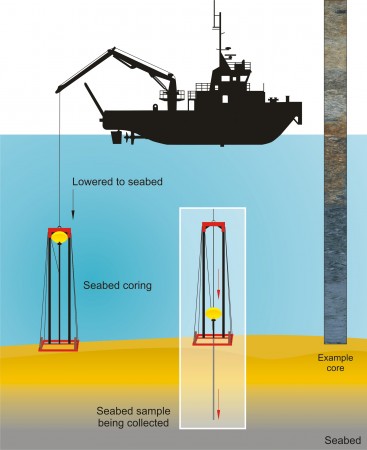

Archaeologists not only examine the physical evidence but they also study a range of historical evidence that can add to their understanding of the past. The first thing they do is look to a variety of national and local government organisations that hold many types of primary and secondary sources of information.

| Sources of Information | What it contains? |

|

English Heritage National Monument Records (NMR) |

The national public archive: 10 million photos, plans, drawings, reports and publications on architecture, archaeology, listed buildings, aerial photographs and social history |

|

Historic Environment |

Regional level public archive |

|

|

Regional level public archive It contains records relating to archaeology and buildings, often developed into the wider HER |

|

United Kingdom |

Contains records on any physical obstructions found on the seafloor, this includes records of known locations of wrecks, including an extensive archive of maritime documents and charts. |

Geophysical Survey

Geophysical Survey

Geophysical Survey is an important element of marine archaeological research.

Archaeologists, like geologists, rely on geophysical data collected prior and during REC to complete their research.

Geophysical survey is used to create images of the seafloor by collecting information about its physical properties. Many companies that specialise in this field employ marine geophysicists and geologists who collect and interpret the information.

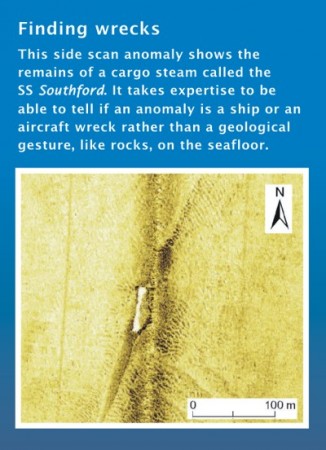

Archaeologists examine the images created by the geophysical data, which show what the seafloor looks like or can provide information about what it is made of. They look out for anomalies, bumps, in the seafloor, that may be ship or aircraft wrecks. They create detailed maps, identifying these locations.

Archaeologists compare these results to historical records about shipwrecks from the NMR. They also compare these maps to information from the UKHO. The UKHO holds records of wrecks and seafloor obstructions around the United Kingdom and has an extensive archive of maritime documents and charts, which record the location of any known seafloor obstruction, including wrecks.

Archaeologists can suggest the identity of a shipwreck from some of this information. Some anomalies have no known information, this suggests that potentially a previously unknown wreck has been discovered.

Geophysics has been very useful for identifying shipwrecks that date from the 19th century onwards, but not quite as good for detecting earlier ships. This is because later ships are substantial and made from metal, which shows up well on geophysical survey.

You can find out more about the individual geophysical techniques and how they work on the ” Geophysical Survey” webpage in this section.

Geotechnical survey

Archaeologists collect samples from deep under the seafloor to find evidence for the past buried underneath its surface.

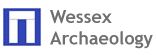

There are many geotechnical survey methods. During the RECs archaeologists used a several of these methods. One of these is  a vibrocorer, which they used to collect samples of sediments from underneath the seafloor.

a vibrocorer, which they used to collect samples of sediments from underneath the seafloor.

This provides information about the different layers of deposits lying underneath the surface, their character and thickness.

The vibrocorer works by vibration. It consists of a long tube, known as a core, around 80 – 90 mm in diameter and between 5 and 6 metres long. First, it is lowered from the boat to the seafloor. Once the core is stable, the motor is turned on, which vibrates the core into the seafloor.

It is allowed to run until either it reaches the end of the core or it hits a hard layer, which it cannot penetrate through. Unlike the Hamon Grab and Clamshell Grab it can penetrate quite hard layers, like clay.

At each sample site scientists collect two cores. One is collected and sealed in a container so it can be dated using a technique called Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL).

In the laboratory the other core is split in half lengthways, for scientists to record sediment grain size, type of sediment, colour of sediment and any other material found within. This material includes shells and bits of wood.

Smaller samples are taken to test for environmental evidence, such as pollen, plants, insects and minute animals. This information is used to identify the environments present in the area when the sediment was laid down.

Like geologists, who also use this technique, archaeologists are interested in how the seafloor formed. This can help them understand what archaeological material may be deposited there.

Archaeologists are interested in the environmental evidence too. They can use this information to reconstruct ancient landscapes, before sea levels rose. Sometimes small artefacts, such as prehistoric flint flakes, created during the production of stone tools can be found in a sample.

Assessing Significance

Once the data is collected archaeologists need to assess the importance of the information they have collected and summarise this in the final report.

One of the key tasks was to assess the importance of individual known shipwrecks.

There are several criteria for assessing the historical importance of a shipwreck. It is dependant on what its potential is for telling us about the past; some ships are so important that they are protected by law. A shipwreck can be a time capsule, recording a snapshot of technology and society at the moment it sank.

The 18th and 19th centuries were a time of innovation in shipbuilding; technological change was rapid. In some cases, a type of ship was only in existence for a short time before technology moved on and new ship types were built.

Many ships were taken apart and some of their parts used to build new ships. Sometimes shipwrecks are the only examples left of their type and can tell us a lot about how shipbuilding changed. In other cases, it is the stories that are attached to the ship and the part it played in history that makes it important.

During World War I and World War II, many ships sank, and some are the final resting place of those who fought or worked on these ships. These are protected places, as they are war graves.

Archaeologists assess those shipwrecks whose identity or types were known, to help us understand their importance. This will inform future measures to protect them as a record of our maritime heritage.

You can read about some of the wrecks identified as significant in the REC’s result webpages.